Term Sheet Recommendations for Launching University Life Science Startups (VC / TTO Roundtable, Spring 2020)

In the Spring of 2020, members from seven university tech transfer offices met with partners from six venture capital firms to discuss challenges both parties routinely face when working on life science deals together. Below is the resulting set of best practices, meant to benefit universities and VCs more broadly. Individuals interested in sharing feedback on the below guidelines should contact [email protected] and include their name, organization, and work email. Please note that not all of these recommendations may be appropriate for startups outside of the life sciences. Comments and feedback will be posted at the bottom of this page.

Participating universities: Columbia (Orin Herskowitz, Ofra Weinberger), Duke (Robin Rasor, Rob Hallford), Johns Hopkins (Christy Wyskiel, Steve Kousouris), MIT (Lauren Foster), Penn (John Swartley), Stanford (Karin Immergluck), Yale (Jon Soderstrom)

Participating VCs: 5AM (Deborah Palestrant), Atlas (Kevin Bitterman), OUP (Bill Harrington), Polaris (Amy Schulman, Alexandra Cantley), RA Capital (Josh Resnick, Sarah Reed, Jamie Kasuboski), Venrock (Cami Samuels)

For context: at first glance, one would think that VCs and university tech transfer offices should be fully aligned. The tech transfer office’s mission is typically to move promising early-stage science-based innovation out of the lab and into the market, while generating reasonable returns which then further the basic research mission of the university and its scientists. The VCs’ mission, meanwhile, is to invest in early-stage innovations that can generate both significant societal benefits as well as economic returns to their limited partner investors. In general, this alignment does in fact exist in reality. Many university TTOs work closely and collaboratively with their venture capital partners, especially when the same VC has invested in multiple startups out of a given institution. Over time, these partners establish strong relationships built on trust; shorten negotiation time by resolving thorny issues once and repeating those outcomes for future deals; and avoid abusive behavior on either side via the promise of positive future interactions.

However, despite this alignment, these discussions often end up being more prolonged, more antagonistic, and more complicated than necessary. This results not only in higher “transaction costs” of getting the deal done (in terms of increased legal bills, more person-hours invested in pointless negotiations, and sometimes scarred relationships), but also in delays around getting the deal done or failure to do so at all. When one considers that many of these innovations could result in saved or extended patient lives, it is easy to see that the costs of the delays go far beyond the economic.

It is easy for both VCs and university tech transfer offices to point fingers at the other side, and in truth in rare occasions there really are “bad actors” to blame. But in our collective experience, most of the friction arises from more systemic issues: disorganized negotiating processes; lack of understanding about the norms for biotech startup deals; misunderstanding of each parties’ core objectives; overcompensating for fear of “making a mistake”. Not surprisingly, when a university tech transfer office and their VC counterparty both have a long track record of startups, and even better when the parties have done deals together previously, many of these issues can be avoided. However, when either or both parties are new to biotech company creation and funding, or haven’t worked together previously, these misunderstanding can quickly devolve into real problems.

Unfortunately, the ramifications from these difficult negotiations can echo far more broadly, with negative implications for the whole VC / TTO industry. Tech transfer offices who feel taken advantage of by a venture investor one time are likely to adapt their practices to protect themselves in the future with other investors, for instance by expanding their license agreements with ever more complex defensive provisions; taking a more aggressive position on their economic “asks” with an expectation of having a long and difficult negotiation; involving even more conservative counsel to ensure that no tricks are being played in the legal terms. Meanwhile, the effected VCs may come to the conclusion that all TTOs (not only the initial one) are simply aggressive and irrational, and hence may either do fewer university-based deals, or else take more aggressive positions and have less trust of reasonable handling in their future deals. Furthermore, both the university and VC communities are quite small and close-knit, and hence these reputational issues can spread beyond even the negotiating parties to the whole profession. Thus, like a mild allergy that worsens with exposure, even some isolated bad experiences can lead to a vicious circle of increasingly negative interactions beyond the initial interaction.

In 3 different Zoom meetings in March to May 2020, we gathered to identify some of the most common pain points encountered by both sides; to discuss the underlying fears and objectives of both sides that might lead to these pain points; and ways these challenges might best be avoided. The collective learnings from these discussions can be found here:

-

A “Recommendations for VC / TTO Term Sheet Structuring” document, see below for text. This document provides an overview of the key issues in university startup term sheets; some best practices for structuring certain sections such as equity, royalties, and milestones; some common points of friction around sublicensing, know-how royalties, and diligence; and other recommendations for how to create win-win outcomes when VCs and TTOs negotiate.

-

A “Recommendations for VC / TTO Negotiation Process Improvements” document, link here. This document provides some recommendations on ways the VCs and TTOs can structure the negotiation process itself to avoid unnecessary friction, gain buy-in early, and avoid overly long and painful negotiations.

These documents were discussed by the participants at AUTM 2021 (recording here) and in a webinar hosted by OUP (recording here).

We hope that these can be useful to the profession, and will lead to more university innovations becoming stronger startups, even faster than they do today!

Our recommendations are as follows:

- Equity

- On the surface, universities use a wide variety of preferred approaches commonly for their VC-funded startups. These often include:

- Mid-single digit equity with anti-dilution through a Series A (sometimes with “through $___M raised”, rather than simply a Series A, given how large A rounds can be in certain circumstances)

- Mid-double-digit starting equity position, but with no anti-dilution protection

- “Change of control” or “synthetic equity” terms (essentially, non-dilutable equity), which provides the university a very low single-digit % or a set fee of exit value upon acquisition change of control at the startup. Note that some VCs are opposed to change of control or other non-dilutable equity, as it can cause complexity in future rounds or at an IPO.

- On the surface, universities use a wide variety of preferred approaches commonly for their VC-funded startups. These often include:

It was noted that this term, as well as the others below where specific ranges are mentioned, are predicated on the company being founded on a single institution’s IP. In situations where the company is being founded initially based on IP being licensed from multiple institutions nearly simultaneously, the ranges here and below may need to be adjusted.

- Most universities will ask for participation rights / rights of first refusal as part of their equity, allowing them to avoid undue dilution in later rounds if they, or their designees, can provide the cash required to invest alongside later investors on the same investment terms. However, very few universities have the financial flexibility to provide these investments within the timeframe required during startup financing rounds. Accordingly, many universities have entered into agreements with Osage University Partners (OUP) to take up these rights. Startups are typically fine with universities having these participation rights and transfer those rights to OUP, with certain caveats. For instance:

- That the university’s equity stake is within the ranges described in 1a above.

- If the participation rights aren’t exercised in a given round (leading to dilution for the university), the participation rights for the next round should only allow the university to retain the percentage of shares it then holds, not the original percentage.

- In oversubscribed future rounds, the university may unfortunately be forced to reduce its participation rights percentage to accommodate other investors. However, it should only be forced to do so at the same rate as the existing investors, not more so.

- Royalties and success-based milestones

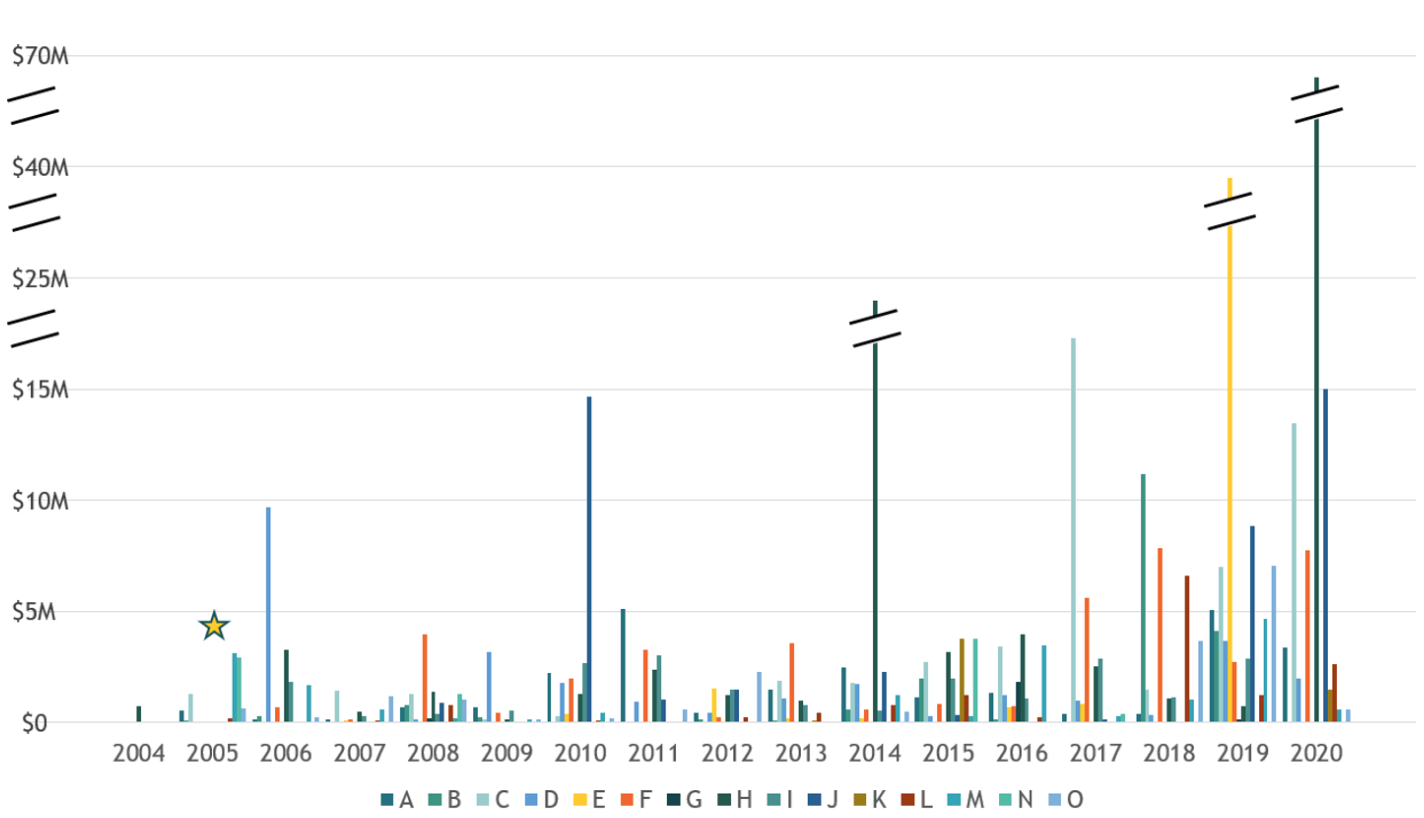

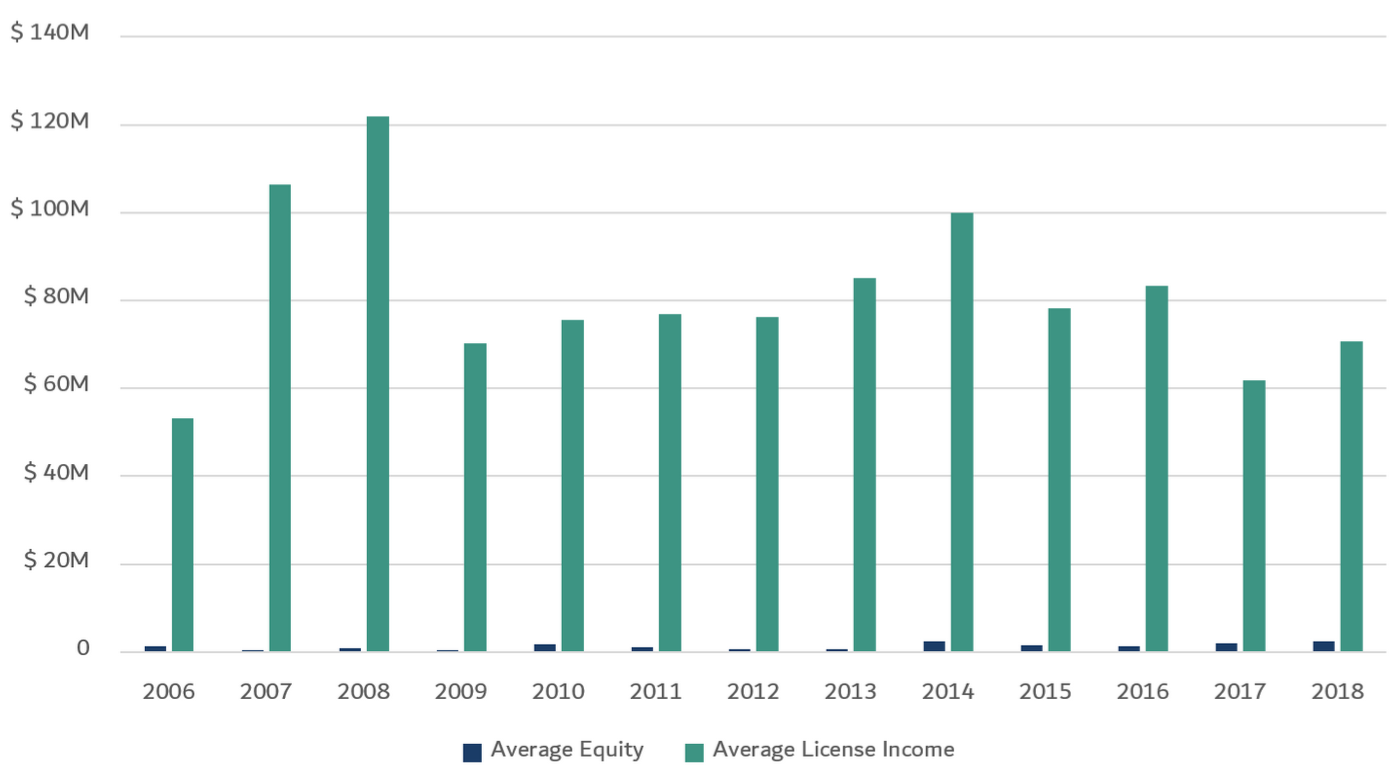

- Of all of the financial deal terms, universities typically care most about royalties and success-based milestones payments, as these (along with sublicensing income, which is addressed separately below) often represent the vast majority of the revenues for successful life science startups. Equity is fantastic, but is typically seen as a time- and risk-adjusted substitute for large upfront and early-year fees that would normally be received if licensed to a big biopharma. As is clear from the charts below provided by OUP, while large equity liquidations do happen, and are increasing, they are not the norm. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the average equity liquidations per year per school are typically significantly lower than the royalty revenues received.

- Fig A: Total Equity Liquidation Per Year, OUP Core Partners

Fig B: Average Equity Liquidation vs. Royalties for OUP Partners, by Year

- As noted above, these equity stakes are usually so diluted by the time of a meaningful exit that they rarely end up representing significant revenues to the university. However, equity is still important to the universities, especially as protection so that university still participates somewhat in the company’s success even when the company pivots away from the university licensed IP, or the company ends up terminating the license. VCs note that while this is generally true, there are situations when the equity dilution is more modest and the path to a liquidity event is faster, where the equity portion ends up being worth tens of millions to the university (as noted in the first figure above).

- Both the VCs and the TTOs agreed that using known, established comparables for royalties and milestones is an excellent approach to establish the general parameters, understanding that financial valuation still depends on case-specific factors, such as the breadth and strength of the IP. Royalty and milestone benchmarking data can be found in various 3rd party sources, such as the Licensing Executive Society surveys, KTMine, TransACT, or pulled from regulatory filings of public companies, or from the TTO’s, VC’s, or their outside counsel’s databases. It was noted by all that royalty rates for therapeutics tend to end up in a fairly tight range already today, depending on the stage of development of the Licensed Products in question.

- However, for the use of benchmarks or databases to be effective, both sides need to resist the temptation to “cherrypick” only those data points that support that side’s arguments. This unfortunately common tactic quickly erodes the trust between the parties, and can lead to negative outcomes both in the negotiation process and the outcomes.

Furthermore, all financials need to be taken in aggregate, not piecemeal. For instance, a deal comp with a particularly low royalty rate might offset above-average equity allocation, or vice versa. Accordingly, when looking at individual comparable deals, the terms need to be looked at in totality. For instance, in bridging the gap between the parties on royalties or other terms, other parameters such as a higher equity stake or larger or more near-term milestone payments may help.

- While large biopharma companies are often comfortable with success-based milestones in the 7- or 8-digit ranges (for regulatory milestones, first commercial sale, etc), based on comparables, these large milestones can often be difficult for even well-funded startups to pay if they haven’t yet partnered with or been sold to Big Biopharma. Accordingly, some universities are structuring their deals to have biopharma-level success-based milestone payments, but including built-in mechanisms to reduce the burden while the company is still truly a pre-partnered startup. For instance, one institution’s model includes success-based milestones appropriate to a startup’s budget, but which increase by a significant multiple upon partnering (at least, when partnering also provides increased access to capital) or acquisition. Another’s model includes success-based milestones that are biopharma appropriate, but allows the startups to defer 90% of each milestone until they are partnered or acquired. See Exhibit A in the appendix for sample clauses for these options. VCs noted that care should be taken that startups don’t end up having to “pay twice” for these success-based milestones when a sublicensee achieves them. If the milestone payments are made directly by the startup, then they shouldn’t also be included in the non-royalty sublicense income under the sublicense clause if made by the sublicensee as well. However, if the milestone payments paid by the sublicensee is larger (say, $1M) than what is contractually obligated to be paid to the university if the startup itself had hit the milestone (say, $400K), then the difference between those two payments (in this example, $600K) would be included in NRSI.

- Startups may be concerned about whether these royalties and success-based milestone payments will significantly reduce their acquisition price in an exit. However, one VC noted that studies have shown that the size of royalties and success-based milestones (as long as within the normal range) do not seem to have a significant impact on exit values. Furthermore, royalties and the largest milestones typically occur after the acquisition, and hence aren’t really “paid” by the startup’s investors. Of course, if royalties requested are outside of the “norms” (based on comparables), then some VCs may choose not to invest.

- Board seats

- Universities occasionally request a board observer seat, to allow access to information about how the company is progressing (even if it is occasionally excluded from confidential board discussions that pertain directly to the university license agreement). The university will also have the opportunity to identify ways it might help the company beyond the agreement: connections to other venture investors; connections to potential junior and senior talent; connections to contract research organizations or university core facilities; opportunities to generate press coverage, if desired. Since the university’s seat is non-voting, it will not directly influence the path of the startup, which would be inappropriate since the university is typically a minority shareholder. Note: the structure described here is for the typical university startup. However, some universities take a more active role in forming some of their startups, including serving as the initial management team until traditional investors sign on. Accordingly, some universities will have voting board seats in these startups, at least initially.

- However, VCs are often uncomfortable having the university’s board observer status continue after institutional investors such as themselves have made their A-round investments. The VCs explained that there is a fundamental conflict-of-interest issue here, since by the time of the VC’s investment or for the following rounds, the company will often be exploring adjacent technologies beyond what was licensed to the university. Having the university involved in these confidential discussions can make it difficult for the board to have truly open conversations. Furthermore, it was noted that it is often not the TTO senior leadership who takes these seats, but rather a licensing associate, so the university’s opportunities to add significant value above and beyond the rest of the board are rarely realized.

- The group suggested that a reasonable compromise might be as follows

- Board observer seat for the university until the completion of the A round by institutional investors, or the first professional VC round whenever that occurs (seed, A, etc)

- Thereafter, the university should relinquish its board observer seat (unless asked to stay on), but should still have a mechanism to receive close-to-real-time information from the startup. The information mechanism could take the form of the meeting notes from the board meetings (redacted if needed) within 30 days of the BoD meetings; quarterly or annual updates from the startup on specific data points, or other mechanisms; and periodic meetings between TTO and Company leadership.

- Of course, none of the discussion above relates to the board seats (if any) for the scientific inventors, rather solely for the university itself.

- Windfall success payments

- As a means for the University to share in resounding company success, some universities are including valuation-based milestones, sometimes referred to as Success Fees, in their agreements, especially as an alternative (or, in competitive situations where there are multiple bidders for the IP, in addition) to when equity is eliminated or reduced. These arrangements, which are typically designed to survive license termination, call for payments of fixed amounts when company valuations cross certain milestones, triggers, or levels, typically starting in the billion-dollar range. These windfall payments can also be an excellent lever to use when there is a gap to be bridged on royalties or sublicensing income. Some VCs noted that these windfall success payments might make more sense when both parties have a high degree of confidence that the university licensed IP will be the primary cornerstone for the company, around which the rest of the company will be built, but less so if the IP is likely to be only one piece of the puzzle. Also both parties should ensure that the payment obligation is only triggered at a time when the company has sufficient liquidity to meet the obligation. The same principles can also be achieved by adding extra warrants with higher prices to the equity grant, as opposed to structuring these as cash payments to be transferred at later dates. An example of the triggers and associated payments is shown below.

- Valuation Trigger

- $0.5 billion

- Success Payment

- $1 million

- Valuation Trigger

- $1.0 billion

- Success Payment

- $3 million

- Valuation Trigger

- $5.0 billion

- Success Payment

- $10 million

- Valuation Trigger

- Success Payment

- Patent prosecution and patent expense reimbursement

Generally, ongoing patent expenses are expected to be paid by the startup, with the university continuing to manage prosecution, and the company sometimes having step-in rights (for exclusive licenses) in the highly unlikely event that the university decides to drop the patent. In some situations, universities may allow the startup to take over prosecution, but only with approval rights for the university on prosecution decisions. Prosecution of new jointly-developed (between the university and the startup) IP is typically managed by the company, with approval rights for the university. Past patent prosecution costs are typically paid upfront in the license, or upon VC investment. If the license is non-exclusive or field / territory limited, then patent prosecution (both past and current) is often shared pro-rata across the number of licensees.

- “Other Products” (aka “Enabled Products”) / Licensed Know-How & Technical Information

- Context: this is one of the most challenging clauses of the license agreement, and the one that most often ends up in dispute years later, occasionally even leading to litigation. Hence, focusing extra attention on ways to ease both the negotiation and the later interpretation of these clauses is worthwhile.

In the vast majority (though not all) of VC-backed university startups, the collaboration between the startup and the university goes beyond a simple license to patents and tangible materials. The faculty and student inventors are typically involved in transferring intangible know-how during the diligence stage pre-license, often act as consultants, advisors, or board members and may participate in research contracts funded by the startup. In addition, employees of the startup may visit the university either for discussions or as visiting researchers.

However, given the informal nature of this collaboration, it can be challenging to define a priori exactly what constitutes a product (beyond Patent Products) on which the university should receive royalties and milestones.

- Context: this is one of the most challenging clauses of the license agreement, and the one that most often ends up in dispute years later, occasionally even leading to litigation. Hence, focusing extra attention on ways to ease both the negotiation and the later interpretation of these clauses is worthwhile.

The university’s biggest fear is that it ends up getting no royalties (which often are the most important financial license term, as noted above) on something that was in reality at least enabled by its researchers. It is not uncommon that a product ends up being successfully launched that doesn’t infringe the originally licensed university patents, but was definitely enabled by the university collaboration. Universities understand that royalties on these non-patent “enabled products” should be lower, but not zero.

Investors and the faculty inventors want the university to be as open as possible in sharing non-patented knowledge, both before and after the license agreement. On the other hand, investors have some concerns about non-patent royalties. In particular, these concerns focus on later stages of the company’s life. For instance, in cases where the startup has entered into a joint venture or been acquired by a biopharma company, there is a fear that a broad enabled products definition could end up leading to royalties being paid on the JV or acquirer’s products, even if those products were initiated prior to the JV / acquisition. There is also a concern that the enabled product definition should not attach to startup products for too long a period, since in most cases the majority of the value would have been transferred during the initial years following the license.

VCs also noted that there might be a meaningful discussion about any know-how and technical information that is initially not disclosed beyond the company, but then later becomes public due to publication, and if / how that impacts other product royalties. They make the point that there is a tension between allowing the university to share in the benefit of their know-how and technical information via the other product royalties (especially for early access to that information), vs. ending up with the startup paying royalties on public information that their competitors don’t have to pay for.

It was also noted that there may truly be situations where the startup is not relying at all on know-how, technical information, or materials from the university, either at launch or thereafter. If so, then the startup should normally be willing to rep and warrant that no such university know-how will be used.

- The parties discussed general principles of how these clauses should be handled, as well as specific language for embedding these principles in the license agreement, as follows:

- General principles for “Other Products / Enabled Products”

- Any products or services developed by the startup within the Licensed Field while there is an active sponsored research agreement with the university, or where the university’s active faculty or graduate students (excluding former faculty or students who have taken a full-time role in the company) are paid consultants or otherwise actively involved in the company, should be assumed to use Know-How, and hence count as Other Products. However, it was acknowledged that mere participation by university staff on the SAB, without any paid engagement or sponsored research, is typically largely ceremonial, and hence shouldn’t necessarily count as a trigger. VCs also noted that the specific determinations here need to be discussed between the parties openly and honestly, to make the funders and the university comfortable with whatever role the university employees end up playing at the company.

- If the startup is approaching an acquisition, or perhaps even periodically throughout the license duration prior to acquisition discussions, the TTO and the startup should review all the active development projects at the startup and determine which projects would be considered Other Products. Once the startup has been acquired in an arms-length transaction, any new projects launched by the startup or acquirer, as well as projects that were already underway by the acquirer, would not count as Other Products. That way, the acquirer won’t have concerns that purchasing the startup will result in a tainting of their existing or future pipeline.

- General principles for “Other Products / Enabled Products”

- Specific language:

- One of the universities has embodied these principles in an approach called “Meaningful Involvement”. However, that specific approach may not work for every university, depending on that institution’s approach to conflict-of-interest regulations. See sample clauses in Exhibit B of the appendix to this document.

- Another university uses an approach that stipulates that if know-how or licensed information is used to support regulatory filings (e.g., included in the IND filing), that automatically triggers a royalty obligation.

- One VC suggested providing an exhibit including a detailed description of the specific know-how, and a definition of Other Products that makes it clear that the Other Product royalties will be paid on products that use the know-how rather than products that were developed or derived from the know how. Universities generally disagree with the narrowing of that definition in this matter, however.

- Open issues relating to Other Products

- It was also noted that the above suggestions might work better for certain types of startups (for instance, when the licensed assets are compositions of matter), and less well for platform technologies. Platform technologies are more complicated, since the know-how, technical information, or materials may turn out to have broad utility across more development projects and for a longer period.

- It was also noted that many of the arguments above would be relevant for joint ventures as and for acquisitions, but this situation wasn’t addressed in the discussions at this point.

- The group will attempt to provide suggestions for these variants in future sessions, and would be interested in feedback from others in our fields.

- Licensing Improvements

- In principle, both universities and VCs are aligned in wanting direct “improvements” generated in the lab of the initial university scientist/founder to be licensed to the startup on fair terms. That way, the startup will have all of the assets it needs to build the strong product lines. However, there can be a variety of challenges in automatically rolling into the license improvements that have not yet been made or disclosed, or that were not actually supported by the startup. These challenges include:

- Perceived conflicts-of-interest whereby there could be a perception that the researchers have an incentive to report positive outcomes and have them licensed to the startup to boost their own equity value

- Perceptions that the university research lab has been “enchained” to the startup, and is therefore just doing outsourced contract research

- Perceptions that new faculty, postdoc and student collaborators not on the initial IP could find their inventions unknowingly pre-committed to a company and also might not participate in any equity value unless additional equity is granted for the improvements

- Some research funding sources (especially certain foundations) may have terms that preclude new inventions based on their funding from being automatically rolled in to a license thereafter

- Automatic rights to future improvements may also cause complications for the faculty’s ability to secure other funding from industry in the future, and hence may limit the progress of their research

- Many universities will allow startups to have a first option to add these narrowly defined improvements (where feasible) into the license, particularly when the startup is providing sponsored funding back to the inventor’s laboratory to support this continued research and development (where that is allowable), but with some restrictions in place to minimize the concerns above. For instance, the automatic licensing provision may include a limitation on the duration for which these improvements may be added (_X_ years from the initial license, or while there is ongoing sponsored research from the company to the university); relationship to initially-licensed IP (only if practice of the improvements would infringe upon a claim within the initially-licensed IP); inventors (only if no new faculty are named inventors, or if the improvement emerges from initial faculty member lab). However, contractual access to improvements is governed by the specific policies and practices of each institution, and hence varies university by university; is sometimes inconsistently allowed by university conflict-of-interest committees; and are often outside of the TTO’s ability to control.

- As mentioned above, one of the universities has pioneered a new approach for these automatic grants of future improvements, under the “meaningful involvement” language mentioned above in the Other Products section. In essence, the “duration” question above (for how long improvements will be automatically included in the license) is explicitly tied to how long the university scientists are “meaningfully involved” in the company, and hence during the “meaningfully involved “period any products or services whose development was initiated during this period would count as Other Products under the license. However, that specific approach may not work for every university, depending on that institution’s approach to conflict-of-interest regulations, so called “private use” IRS restrictions, etc. See Exhibit B in the appendix for one example of how to structure such clauses.

- In principle, both universities and VCs are aligned in wanting direct “improvements” generated in the lab of the initial university scientist/founder to be licensed to the startup on fair terms. That way, the startup will have all of the assets it needs to build the strong product lines. However, there can be a variety of challenges in automatically rolling into the license improvements that have not yet been made or disclosed, or that were not actually supported by the startup. These challenges include:

- Field of use / diligence clauses / minimum royalties and annual payments / mandatory sublicensing

- In university license agreements, there is an inherent linkage between the breadth of the licensed field of use on the one hand, and the university’s ability to ensure that the invention gets maximally used on the other hand. In terms of the field, startups typically want the broadest possible rights to the invention: exclusive rights to all fields and in all territories.

Universities will usually try to accommodate that need, but want to ensure that any subfields or subterritories that end up not being pursued by the startup in a reasonable timeframe will be developed by other parties (either via sublicense or by being returned to the university for re-licensing). This is consistent with guidance from Federal grants, the principles embedded in the Bayh-Dole Act, and the university mission to ensure the broadest possible use for new inventions.

Three contract terms by which the universities can ensure this happens are: 1) diligence terms (which need to be reached to keep the licensed fields/agreement active); 2) minimum annual royalties and/or annual maintenance fees (which create an incentive to the company to release unused IP to avoid these payments), and 3) mandatory sublicensing terms.

Unfortunately, VCs and startups naturally resist having diligence terms in the license that are firm and binding, since the prospect of losing some or all rights at later dates is naturally unappealing. Similarly, startups would prefer that minimum annual payments be low, to preserve cashflow. Furthermore, allowing sublicensing of unused fields on the same technology can be challenging, since the startup may be concerned that an unrelated sublicensee may end up competing with the startup, thereby causing confusion in the marketplace, or generating contradictory data from parallel clinical trials not under the initial startup’s control. Accordingly, negotiating these terms can be quite challenging. VCs therefore typically prefer that diligence milestones be based on investment and efforts applied, not necessarily outcomes so that the company, after investing significant resources, won’t inadvertently lose rights solely due to one experiment with a negative outcome.

- In university license agreements, there is an inherent linkage between the breadth of the licensed field of use on the one hand, and the university’s ability to ensure that the invention gets maximally used on the other hand. In terms of the field, startups typically want the broadest possible rights to the invention: exclusive rights to all fields and in all territories.

For startups, there is also a timing element. In the early years, flexibility is needed when the startup doesn’t yet know exactly which products it will pursue or in what order. Similarly, cash will be tight in the early years, so high minimum annuals are difficult. Over time, however, the startup should live with returning unused fields for exploitations by others or pay significant minimum annuals to avoid having to return those rights.

A few ways to address these challenges may include:

- Allowing missed diligence milestones to be extended for a certain number of months, either for a limited number of instances across the agreement’s life, or else for escalating fees each time. The clause may give a specific number of months of extension, or specify that the parties will reasonably negotiate an appropriate extension. There also may be a provision that if the IP is sublicensed to a biopharma partner, the license will not be terminated as a result of the missed diligence milestone (which can otherwise result in too much risk for Big Pharma). These extensions may also trigger a matching extension of the duration of Other Product Royalties specified under the agreement, due to the delays.

- Having the minimum annual payments required in order to keep the license active start small in the early years, but escalate significantly over time

- Providing a narrower field of use initially, but providing time-limited options to the startup in order to add fields to the license (for a fee) later in the agreement as long as progress is being made or other triggers

- Some agreements may end up containing mandatory sublicensing provisions, under which the startup may be required to provide mandatory sublicenses to 3rd parties for any fields that they are not pursuing or choose to not pursue upon notice from the university of an interested 3rd party. These clauses may become active only after a few years, to allow the company time to determine its own path to market. VCs noted that the mandatory sublicensing approach is less common / rarely seen, and requires care in execution. However, one clear benefit of the mandatory sublicensing approach is that the startup faces an erosion of its field of use only if and when there is an actual third party interested in exploiting some aspect of it.

- Including a reasonable definition of “commercially reasonable effort”, to avoid the startup failing milestones due to truly unavoidable situations. It was noted that determining what a “commercially reasonable effort” entails may be challenging. If so, it may be necessary to include dispute resolution measures (e.g., binding arbitration) if the company disputes a claim by the university that it has not used commercially-reasonable efforts to complete the milestones.

Unfortunately, the incentive misalignment around these topics makes it challenging to recommend a “one size fits all” approach. However, for an example of how the mandatory sublicense clauses have been addressed by one institution in partnership with some of the VCs represented, please see Exhibit C in the appendix to this document.

- Sublicensing

- Sublicensing is one of the more complicated portions of the university startup license. Startups want to retain full flexibility to sublicense the licensed IP for the benefit of the shareholders:

- Either alone or in combination with company IP

- To whichever partners the startup deems best without university approval, and through as many tiers as necessary

- To use the sublicensing revenue however it sees fit

- Universities are typically happy to allow the startup to sublicense within reasonable parameters, but have the following concerns:

- That the university is made aware of any sublicenses that are executed, at least shortly after execution if not in advance of the sublicense

- That all sublicensees are bound by the terms of the underlying license

- That the university shares appropriately in any revenue received from the sublicensee, regardless of the structure, type of payment or timing

- That if the license terminates, the sublicensee may not automatically stay in place

- Sublicensing is one of the more complicated portions of the university startup license. Startups want to retain full flexibility to sublicense the licensed IP for the benefit of the shareholders:

The reason “appropriately” is emphasized above is that determining what is appropriate can be quite challenging. While it is true that the university is an equity holder, universities often end up with equity in the low single digits by the time sublicensing is contemplated, and the university invention may be only one of many product lines being developed. Accordingly, universities will typically try to ensure:

- That the university shares in non-royalty sublicensing income (NRSI) at a higher % initially, declining to a lower % as the licensed technology is developed, determined at the time the sublicense is executed. (The logic here is that the relative contribution of the university’s IP is likely higher in the early development of the technology, and that the investment made by the startup is also smaller in the earlier years and increases as the technology passes certain technical hurdles.)

- That there are disincentives for the startup to simply “flip” the IP via a sublicense within the first ~12 months of the license, by having a very high first tier during that timeframe. However, VCs noted that there are certain circumstances wherein it is in everyone’s best interest to allow the startup to enter into limited sublicense agreements even in the first 12 months as a fundraising strategy. In these circumstances care should be taken to not penalize that outcome inappropriately.

- That the university’s share is based on NRSI regardless of format (cash, equity, etc), and determined by the effective date of the sublicense (as opposed to when the startup actually receives the sublicense revenue). It was noted by the VCs that whether this is appropriate seems highly subject to the terms of the relationship between the startup and the sublicensee.

- If the university’s IP is sublicensed alongside the company’s IP, that there is a structure for determining the relative contribution between them, and that there is a floor below which the university’s share cannot fall.

- That any deductions for R&D the company is allowed to take from NRSI before sharing with the university are solely to advance the university’s products.

- On the other hand, VCs and startups may see these requests to share in NRSI as “double dipping”, since the university is already receiving both equity (albeit small amounts) and royalties. Universities typically reply to these concerns by pointing out that these sublicensing questions only arise because the university is (at the startup’s request) usually licensing far broader fields than are initially required (see the “Field of Use” discussion above), and hence sharing in NRSI is a way of sharing some of the breadth-of-field benefits back with the university (though one VC argued that the company is often only able to sublicense in these additional fields due to having achieved proof-of-concept in the original field). In addition, sublicensing revenue almost always occurs well before any royalty payments and reflects revenue received by the company for value in the university licensed IP, and since the vast majority of the university’s revenue terms are back-ended, the university should share in these nearer-term payments as well. Furthermore, the universities argued that the concept of the university sharing in NRSI is, at this point, simply a market-rate term. Hence, if they are to be removed on a case-by-case basis, then that value should be returned elsewhere in the agreement.

- Another complication is what happens when the university IP is sublicensed alongside the startup’s own IP. In these situations, it can be complicated to determine an appropriate relative apportionment of value between the two different bundles of sublicensed IP, and hence against what base the university’s NRSI should be applied. By way of example, if one university patent is sublicensed alongside two startup patents, the university may argue that the university’s NRSI % should be applied to 1/3rd of the total NRSI value received, whereas the startup may argue that the university’s NRSI % should be applied only on 10% based on a qualitative assessment of relative value from the patents. As mentioned above, there may be a floor that is applied, below which the university’s portion cannot fall.

- Unfortunately, given the difference of opinion on this topic, negotiations on this point can lead to significant friction. In addition, the temptation can be high for the startup to “play games” with sublicensing income by calling it something else, or adding unnecessary IP to the sublicensed bundle, or making inappropriate deductions. Having seen these outcomes previously, universities may start off being highly rigid and expansive in trying to capture NRSI. Accordingly, sublicensing terms end up being among the more challenging to negotiate during the license, and one of the most frequent subjects of post-execution lack of trust and even litigation.

- While our group was unable to provide a single, best-in-class approach, there were some guidelines that the group could agree upon:

- The NRSI % may start high immediately following the license execution, essentially as an “anti-flip” tax to discourage the startup from taking more fields than needed;

- However, the NRSI % should decline, based either on time, on progress, or on the venture investment put to work in the startup. Exactly how low the % should eventually go was a matter of open debate still;

- Allow deductions from NRSI for R&D expenses, but only for direct expenses used to advance University Products specifically. There was disagreement as to whether past expenses should be allowed to be deducted, vs. only future expenses specifically earmarked and reserved for the startup’s R&D. Some VCs also questioned whether R&D expenses should be deducted for all products, not just the university products; the universities countered that if the NRSI is being apportioned to reflect the relative value of the sublicensed university IP vs. the company’s sublicensed IP, then the sublicense payments back to the university should only be reduced by R&D expenses for university products.

- NRSI should be based on any type of value received in exchange for the sublicense (cash, equity, etc).

- As mentioned above, development milestone payments should either be paid under the license agreement, or as NRSI, but not paid in both places (i.e., no double dipping)

- If tiers exist for the NRSI, the relevant tier should be calculated based on when the sublicense is executed, not when the revenue is received, to avoid gaming the revenue recognition in order to select a lower NRSI % tier (for instance, by delaying payment until after a milestone is achieved, and hence assigning that revenue to a lower NRSI tier);

- There should be one of the two following approaches to determining the appropriate apportionment between university IP and startup IP in a sublicense:

- Either there should be a clear and consistent approach to determining the relative apportionment between sublicensed university IP and startup IP; a floor below which it cannot be apportioned; and a dispute resolution mechanism escalating to using external independent input should the apportionment approach be subject to disagreement

- Or the license agreement should have significantly lower numbers for the university’s share of NRSI, but that % should be immune to apportionment. In this approach, the university will receive its NRSI % on all sublicense deals, regardless of whether the university sublicense is sublicensed alone or alongside the startup’s IP

Appendix

Exhibit A: examples of scaling up startup success-based milestone payments upon acquisition or partnering

Example 1: multiplier of milestones upon partnering / acquisition:

Change of Control Multiplier. In the event of a CHANGE OF CONTROL and/or a permitted assignment in accordance with Article 10, any milestone payment set forth in this Section 4.1(i) that has not yet come due shall be increased by three hundred percent (300%) (“Change of Control Multiplier”).

Example 2: postponement of milestones due until Trigger Event:

However, until a Trigger Event as defined below has occurred, Company shall owe only __% of the above milestones when milestones are due. The remaining unpaid ___% the above milestones that would have been due had a Trigger Event occurred (“Deferred Payment”) will be due within 30 days of the date of the occurrence of a Trigger Event. A “Trigger Event” means any of the following:

- Company has had more than [$XX,000.00] _______ thousand dollars in cumulative Net Sales of all Product(s); or

- Company completes a financing or a series of related financings in which it has sold and issued shares of its capital stock with aggregate gross cash proceeds to the Company of at least ___million dollars ($__,000,000),

- Company has entered into a “Strategic Agreement” with a Third Party concerning the manufacture, research, development, marketing, use and/or sale, of any Product(s) (collectively, “Strategic Activities”), including any Third Party funding of Company for any of those Strategic Activities. For this Subsection 6a(iii)C, “Strategic Agreement” means any of the following:

- an informal agreement or understanding (including Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Understanding, Heads of Agreement, or similar writing or understanding) related to the Strategic Activities, or

- a formal written binding agreement(s) related to the Strategic Activities; including any alliance, joint venture, partnership, co-marketing and/or sales force agreement or arrangement between Company and a Third Party that is not de minimis in substance regarding any Strategic Activities; or

- The Company has entered into any “Strategic Equity Agreement” with a Third Party. For Subsection 6a(iii)(D), “Strategic Equity Agreement” means that a Third Party that is engaged in the business of manufacture, use and/or sale of products for the prevention, treatment, mitigation, and/or diagnosis of disease, including pharmaceuticals, biologics (including antibodies, interleukins, and vaccines), medical devices, tissue, tissue products, and/or any tests or kits related thereto, which actually or beneficially owns more than fifteen (15%) percent of the equity or debt securities of Company; or

- The Company has entered into any “Change of Control.” For purposes of this Subsection (E), “Change of Control” means any transaction or event or multiple transactions or events (including, without limitation, a merger, other business combination, share exchange, spin-off, liquidation or reorganization) as a result of which all or substantially all of the Company’s assets are sold, leased, licensed or otherwise transferred, or a change of control occurs or if there is an initial public offering of any securities of the Company. In addition, a Change of Control includes any transaction or event or multiple transactions or events following which the holders of the voting shares of the Company before the first such event no longer hold (in substantially the same percentages) a majority of such shares of the Company or any successor (without giving effect to any shares acquired by the holders in the Company or such successor other than as a result of ownership of the shares of the Company before such event).

Exhibit B: “meaningful involvement” re: licensing improvements

SAMPLE CLAUSE -- While Dr. XYZ is MEANINGFULLY INVOLVED with both LICENSEE and INSTITUTION, INSTITUTION shall notify LICENSEE of any invention, whether patentable or not, invented in the laboratory of Dr. XYZ, that is in the FIELD, disclosed to INSTITUTION’s Office of Cooperative Research, that LICENSEE does not then have rights to under the LICENSE, that is owned or controlled by INSTITUTION, and that would otherwise be dominated by, incorporates or uses the LICENSED PATENTS as listed in Appendix A on the EFFECTIVE DATE (an “IMPROVEMENT”). INSTITUTION shall amend this Agreement to include such IMPROVEMENT as LICENSED INFORMATION or a LICENSED PATENT, as appropriate, subject to the rights of any non-profit sponsor of the research leading to such IMPROVEMENT (which sponsor, except for the United States federal government, shall not have the right to license, sublicense, assign or otherwise grant such rights to any person or entity, other than for non-profit purposes, and not for purposes of commercial development, use, manufacture or distribution); provided that LICENSEE acknowledges and agrees that to the extent that any IMPROVEMENT is jointly owned by INSTITUTION and another institution, the license to LICENSEE with respect to such IMPROVEMENT shall grant only INSTITUTION’S interest in such IMPROVEMENT. Following a CHANGE OF CONTROL, unless LICENSEE (or its successor or assignee) makes a CONTINUATION ELECTION within [**] following such CHANGE OF CONTROL, LICENSEE’S (or its successor’s or assignee’s) rights under this Article ___ shall terminate upon the expiration of such [**] period; provided that if LICENSEE (or its successor or assignee) makes a CONTINUATION ELECTION within such [**] period, then LICENSEE’S (or its successor’s or assignee’s) rights under this Article ____ shall continue in full force and effect. The lab of Dr. XYZ at INSTITUTION shall not conduct any sponsored research, collaboration or other similar arrangement in the FIELD (a) with any for-profit company while Dr. XYZ is MEANINGFULLY INVOLVED with LICENSEE, other than with [**] under the terms of the [**] or (b) with any person or entity unless INSTITUTION retains the right to grant LICENSEE the rights set forth in this Article ____

Exhibit C: “mandatory sublicensing”

If, at any time after three (3) years from the Effective Date, INSTITUTION or Company receives a bona fide request from a Third Party seeking a license under the Patent Rights to develop and commercialize a Licensed Product (the “Proposed Product”), then the party receiving such inquiry will notify the other party in writing within thirty (30) days of such inquiry (a “Patent Rights Inquiry Notice”), setting forth the specific license under the Patent Rights desired, the name and contact information of the Third Party, the Proposed Product, and any other pertinent information relevant to the Proposed Product. Within nine (9) months after the date of receipt of a Patent Rights Inquiry Notice, Company shall:

(i) reasonably demonstrate to INSTITUTION that (1) the Proposed Product would be directly competitive with a Licensed Product for which Company or a Sublicensee has already begun a Fully Funded project and is diligently developing or commercializing, or (2) Company, or Sublicensee, has already begun a Fully Funded Project for the Proposed Product and is diligently researching, developing and/or commercializing the Proposed Product. As used herein, a “Fully Funded Project” shall mean a development project for a specific Licensed Product at a level of funding no less than two hundred and fifty thousand dollars ($250,000) for the first and second years of the project, five hundred thousand dollars ($500,000) for the third year of the project and one million dollars ($1,000,000) per year thereafter , ending upon First Commercial Sale of such Licensed Product; or

(ii) provide INSTITUTION with a business plan with mutually acceptable, reasonable diligence milestones (such diligence milestones to be added by amendment to this Agreement) for the commercial development of the Proposed Product, which shall include commencing a Fully Funded Project for the Proposed Product within one (1) year of receipt of the Patent Rights Inquiry Notice; or

(iii) negotiate in good faith with such Third Party and enter into a Sublicense agreement containing commercially reasonable terms and conditions for the requested sublicense under the Patent Rights for the Proposed Product. Notwithstanding the foregoing, in the event that Company and the third party continue to make reasonable progress in such negotiations, Company may request to extend the nine (9) month period, as needed, for up to an additional three (3) months to conclude such negotiations.

If Company does not perform any one of the foregoing three actions within nine (9) months after the date of receipt of a Patent Rights Inquiry Notice, then INSTITUTION, at its sole discretion, may grant a license to such third party under the Patent Rights for the applicable Proposed Product within the Drug Field, and upon the effective date of such license, Company’s rights under the Patent Rights for the applicable Proposed Product within the Drug Field shall be terminated, and this Agreement shall be amended to reflect the same. For the avoidance of doubt, if such a license is granted by INSTITUTION, Company’s rights under the Patent Rights for all uses other than for the applicable Proposed Product within the Drug Field shall remain in accordance with the terms of this Agreement.

Comments

From Larry Loev, CEO of ASI (Ariel Scientific Innovations, Ltd.):

Your TS guideline document is terrific, and certainly helpful. I think there are a couple of additional thorny issues that arise in negotiating term sheets, and it would be nice if these were addressed as well:

- Royalty buyout – This issue is usually floated for the situation where an M&A occurs and the acquiring company wants to disconnect from the university, by either stopping royalties entirely, or forcing a royalty buyout. We consistently run into friction on this, and have yet to find a decent formula in advance to determine a fair royalty buyout. In the best case (for the TTO) , we just commit to consider an offer. In the worst case, there may be forced arbitration on this.

- Transfer of IP ownership – Companies like to have IP ownership; it becomes a realizable asset. TTOs don’t like to relinquish it. So this is another point of contention. We have usually been able to solve this by offering IP assignment after the company has either had a certain amount of sales, or paid a pre-determined sum. The justification being that they have fulfilled their obligation of diligence with the technology. BTW, if other licenses have been granted to the IP, they commit to maintaining them.

I’d love to see some comments on how the VCs view these issues and their suggestions on how to solve them.